An architectural exhibition linking light exposure to health

|

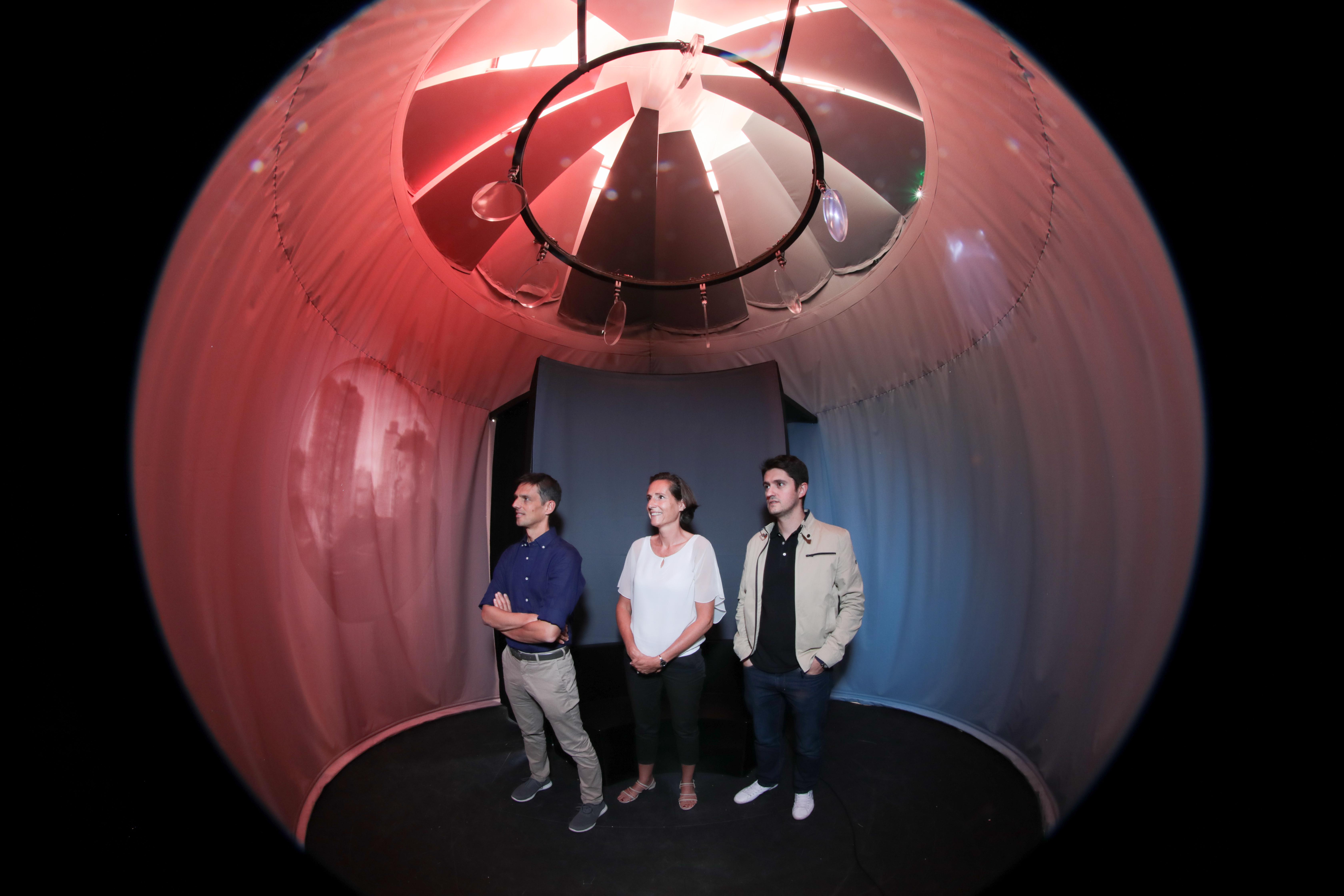

| 2021 EPFL / Alain Herzog - CC BY-SA 4.0 |

Natural light plays a crucial role in the regulation of our circadian rhythms, which dictate a variety of biological processes, from sleep/wake cycles, our level of alertness and even hormone production. This happens because of a photoreceptor called melanopsin present in our eyes and which was discovered only around 20 years ago, making it a still relatively novel research topic. Moreover, our exposure to light is highly dependent on the architecture of the buildings and the cities we live in.

That is precisely what Circa Diem (“about a day” in Latin) aims to highlight with a structure designed and assembled on the EPFL campus this summer 2021. Set-up by researchers from EPFL and HEAD-Genève (Haute Ecole d’Art et de Design), it tackles the relationship between architecture, sunlight and the impact of their dynamics on human health. “People living in cities spend close to 90% of their time indoors and are usually deprived of natural light,” explains Marilyne Andersen, initiator and co-creator of the project, who heads the Laboratory of Integrated Performance in Design (LIPID) at EPFL. “It can make them feel more sleepy, less alert and even impact their immune system.”

The installation thus aims to sensitise the public to the importance of being exposed to enough sunlight for these natural systems to function in an optimal way. It is not only the product of scientific research on neurophysiology but also of cutting-edge optical technology from EPFL’s Geometric Computing Laboratory, headed by Mark Pauly, and Rayform, a spin-off from that lab. The researchers use so-called caustic plates, carefully crafted freeform lenses that re-direct light rays to form clearly discernible images. This innovation enables an entirely new way of immersive story-telling, exemplified with seven typical scenes of urban day-night cycles. “In Circa Diem, we push light shaping technology to its limits to create a unique visual experience. At the same time, the installation highlights the potential for architectural design to reconnect us to our circadian rhythms by re-directing sunlight deep into urban spaces” points out Pauly.

Equipped with a multitude of optical devices, Circa Diem allows visitors to experience in around 7 minutes the 4 phases of the day: morning, midday, evening and night, thanks to changing colours, refracted imagery and lights. Additionally, the top of the structure aims to simulate a high-density skyline around you – an “urban canyon” – reminiscent of dense urban areas with architectural properties not so friendly to having sufficient access to light from the sky. “CIRCA DIEM epitomizes the importance of natural light in human physiology and architectural design, displaying scientific innovations in a pavilion that is deliberately primitive in its formal simplicity and extremely contemporary in its use of technology and materials. After a threshold of intimacy, visitors are embedded into an immersive space whose very material is light and its performance through the lenses,” says Fernandez Contreras.

|

The Circa Diem project will be exposed from September 16 to October 31at the Seoul Biennale for Architecture and Urbanism in a hybrid form: a totemic structure of the same dimensions and volume as the one described, but in which a virtual version of the experience will be displayed instead as the ongoing pandemic ultimately prevented the team to build the full installation on site.

Beyond the exposition, Andersen’s lab will keep exploring the impact of lighting conditions on humans’ health. Simple tips can already be applied in everyday life:

“One habit we have is to leave the blinds down all the time, because we had a glare at some point in the morning. This is actually very bad for your health!” Andersen explains. Piled up on her desk are boxes full of light sensors, ready to be used in a local study on light exposure and commute mode, then sent to classrooms in Iceland for a next chapter of her research, which will compare groups of students living in different lighting conditions. “There has been a lot of work on what to measure to advance knowledge in this field. Now that we have developed a sensor that can, we are going to do so,” concludes Andersen.

Author: Marwan El Chazli

Source: EPFL (CC BY-SA 4.0)